Xiiii

вторник 07 апреля

Louis XIV, king of France (1643–1715) who ruled his country during one of its most brilliant periods and who remains the symbol of absolute monarchy of the classical age. He extended France’s eastern borders at the expense of the Habsburgs and secured the Spanish throne for his grandson.

| Full title | Portrait of the Comtesse Vilain XIIII and her Daughter |

|---|---|

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David |

| Artist dates | 1748 - 1825 |

| Date made | 1816 |

| Medium and support | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 95 x 76 cm |

| Inscription summary | Signed; Dated |

| Acquisition credit | Bought, 1994 |

| Inventory number | NG6545 |

| Location | Room 45 |

Portrait of the Comtesse Vilain XIIII and her Daughter

This portrait is one of the first painted by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) when he chose exile in Brussels in 1816 following the fall of Napoleon, whom he had supported, and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. Isolated from Paris, David relied mainly on painting portraits of Brussels citizens and fellow Napoleonic émigrés to earn a living.

David rarely painted portraits of families and children. Here he captures the affection between the Comtesse, Sophie, and her five-year-old daughter, Marie-Louise, but without sentimentality or idealisation. This restraint and realism are echoed in the plain background and absence of lavish accessories or furnishings.

Fire emblem fates revelation team. The Comtesse Vilain XIIII had formerly been a lady-in-waiting to the Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon’s second wife, and had attended the baptism of their son, Napoleon II, the King of Rome.

There are only two paintings by David in Britain – this, and the National Gallery’s Portrait of Jacobus Blauw.

Jacques-Louis David painted portraits throughout his career, but family portraits, including those of mothers and children, are rare. Portrait of the Comtesse Vilain XIIII and her Daughter dates from 1816, the first year of David’s exile in Brussels following the fall of Napoleon, whom David had supported. Images of motherhood and maternal affection had been popular in French art since the 1780s. However, unlike such precedents, David’s picture does not depict a full embrace or kiss, but is an unsentimental scene of restrained affection rather than overt emotion.

The Comtesse, Sophie, and her five-year-old daughter, Marie-Louise, form a simple triangle set within a shallow space. A number of subtle echoes and contrasts are at work within this basic format: mother and daughter have almost identical hairstyles and wear similar dresses. The seated Comtesse is static and contemplative, her gaze focused on a distant point beyond the viewer. Marie-Louise’s pose, however, hints at movement. Standing, she leans back into her mother’s lap while tilting her head slightly in the opposite direction. Unlike her mother’s, her gaze directly meets our own. This combination of complementary active and passive elements is particularly evident in the hands. As Marie-Louise clasps her mother’s right hand with her right hand, the gesture is reversed on their left where it is Marie-Louise’s hand that is being held.

Despite the physical connection between mother and daughter, their interaction is subdued. David reinforces the impression of the Comtesse supporting her young daughter by draping the orange cloak over the chair and around the Comtesse’s right arm. The orange cloth complements the deep Prussian blue of the dress and brings warmth to the picture. These vivid and intense areas of colour, laid down in thin glazes, also reflect the impact of David’s renewed acquaintance with Flemish painting during his Belgian exile. David includes a variety of materials and fabrics, such as lace, linen and velvet. However, the absence of jewellery is noteworthy. Tellingly perhaps, given the political climate after Napoleon’s fall, the Comtesse does not wear the lavish necklace he had given her.

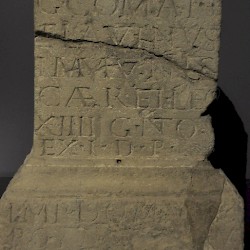

Like David, the Comtesse Vilain XIIII was connected to the Napoleonic cause. Her husband, Philippe Vilain XIIII had been Mayor of Ghent and was ennobled by Napoleon in 1811 (the numerals XIIII originated from an ancestor who had presented the keys to Ghent to Louis XVI). The Comtesse herself had formerly been lady-in-waiting to the Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon’s second wife, after whom she named her daughter.

The Comtesse most likely commissioned the portrait directly from David, and five letters she wrote to her husband between May and July 1816 provide a rare insight into David’s working method. Complaining about the long sittings, typically over four hours, in the painter’s studio and of David’s meticulous approach, the Comtesse – who was pregnant with her fourth child – noted, ‘I must admit that the whole things is becoming boring’ and that she did not find the ‘wretched’ David appealing. Significantly, the letters make no mention of her daughter. Close examination of the painting reveals that she was a late, but easily accommodated, addition. Despite the lack of rapport between sitter and artist, the Comtesse declared that she was very pleased with the finished picture.

Download a low-resolution copy of this image for personal use.

License and download a high-resolution image for reproductions up to A3 size from the National Gallery Picture Library.

License imageThis image is licensed for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons agreement.

Examples of non-commercial use are:

- Research, private study, or for internal circulation within an educational organisation (such as a school, college or university)

- Non-profit publications, personal websites, blogs, and social media

The image file is 800 pixels on the longest side.

As a charity, we depend upon the generosity of individuals to ensure the collection continues to engage and inspire. Help keep us free by making a donation today.

You must agree to the Creative Commons terms and conditions to download this image.

The Dutch patriot, Jacobus Blauw (1756–1829), played an important role in the foundation of the Batavian Republic in 1795. Although short-lived, it significantly contributed to the transformation of the Netherlands from a confederated structure into a democratic unitary state.Blauw and the artist..

The set of basic symbols of the Roman system of writing numerals

The major set of symbols on which the rest of the Roman numberals were built:

I = 1 (one); V = 5 (five);

X = 10 (ten); L = 50 (fifty);

C = 100 (one hundred);

D = 500 (five hundred);

M = 1,000 (one thousand);

For larger numbers:

(*) V = 5,000 or V = 5,000 (five thousand); see below why we prefer this notation: (V) = 5,000.

(*) X = 10,000 or X = 10,000 (ten thousand); see below why we prefer this notation: (X) = 10,000.

(*) L = 50,000 or L = 50,000 (fifty thousand); see below why we prefer this notation: (L) = 50,000.

(*) C = 100,000 or C = 100,000 (one hundred thousand); see below why we prefer this notation: (C) = 100,000.

(*) D = 500,000 or D = 500,000 (five hundred thousand); see below why we prefer this notation: (D) = 500,000.

(*) M = 1,000,000 or M = 1,000,000 (one million); see below why we prefer this notation: (M) = 1,000,000.

(*) These numbers were written with an overline (a bar above) or between two vertical lines. Instead, we prefer to write these larger numerals between brackets, ie: '(' and ')', because:

- 1) when compared to the overline - it is easier for the computer users to add brackets around a letter than to add the overline to it and

- 2) when compared to the vertical lines - it avoids any possible confusion between the vertical line ' ' and the Roman numeral 'I' (1).

(*) An overline (a bar over the symbol), two vertical lines or two brackets around the symbol indicate '1,000 times'. See below..

Logic of the numerals written between brackets, ie: (L) = 50,000; the rule is that the initial numeral, in our case, L, was multiplied by 1,000: L = 50 => (L) = 50 × 1,000 = 50,000. Simple.

(*) At the beginning Romans did not use numbers larger than 3,999; as a result they had no symbols in their system for these larger numbers, they were added on later and for them various different notations were used, not necessarily the ones we've just seen above.

Thus, initially, the largest number that could be written using Roman numerals was:

- MMMCMXCIX = 3,999.